|

|

- Search

| J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs > Volume 29(2); 2020 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine factors associated with nicotine addiction and coping skills in the Synthetic House-Tree-Person Drawing Test.

Methods

This was a descriptive correlational study. The S-HTP drawings were scored using the Buck’s quantitative scoring manual. Participants completed the revised Multidimensional Coping skills questionnaire and the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale.

Results

Non-smokers sketched additional decorations of a house (p=.009), 2D body parts (p<.001), and proportioned body parts (p=.001) as compared to the smokers (n=186). Smokers sketched a more disproportionate stem and branch (p=.010) and did not sketch the nose, lips, or eyes, and generally sketched 1D body parts as compared to the non-smokers (p=.001). There were correlations among the S-HTP drawings, nicotine addiction, and coping skills. The lack of additional decorations of a person, disproportionate house parts, and a lack of proportionate body parts explained 26% of the nicotine addiction (adjusted R2=.26, p<.001).

John Buck developed the House-Tree-Person (H-T-P) projective drawing technique to “obtain information concerning the sensitivity, maturity, flexibility, efficiency, the degree of personality integration, and interaction with the environment,” both specific and general [1]. Mikami then developed the Synthetic H-T-P (S-HTP) drawing test in 1995. Compared to the H-T-P test, which requires the subject to draw a house, a tree, and a person on separate sheets, the S-HTP uses only one sheet for all three drawings [2]. The S-HTP requires less time to draw and show the ability to integrate objects [3]. The S-HTP test, which is one of the projective tests, complements self-report questionnaires by exhibiting unconscious/conscious self-image and family relationships [3], giving insight into patients' problems, and facilitating rapports with patients [4]. In this study, the S-HTP was used to motivate participants for smoking cessation by interpreting the strengths and weaknesses shown in the drawing.

H-T-P drawing test has been used in patients with schizophrenia, addiction, trauma, anxiety, and depression [5-9]. Some researchers used qualitative methods to examine the characteristics of H-T-P drawings by people with computer and drug addictions [8], by children who experienced earthquake [10], and by prisoners with anxiety [9]. Other researchers used quantitative methods to examine the correlations and differences between H-T-P drawings and positive and negative symptoms [6] and resilience [11]. There is a lack of study to examine relationships between the S-HTP drawings and nicotine addiction.

People with nicotine addiction tend to use more emotion-focused coping than problem-focused coping as compared to non-smokers [12]. Smokers who successfully quit smoking for one year coped stress actively, determined, and interpreted positively compared to smokers who failed smoking cessation [13]. Smokers who wanted to quit used coping strategies such as accepting responsibility, self-control, and distancing to endure craving [14]. H-T-P drawings could be beneficial for smokers who want to quit the habit of understanding themselves. There is a lack of studies on the relation between S-H-T-P drawings, nicotine addiction, and coping skills.

Webpage advertisements and flyers were used to recruit participants in a university from September 2013 to February 2017. This study was conducted in the Republic of Korea.

Inclusion criteria for smokers were adults who were older than 19, had been smoking for at least six months, could complete questionnaires, and wanted to quit smoking. Inclusion criteria for non-smokers were adults who were older than 19, had never smoked cigarettes, and were not addicted to alcohol, games, and smartphones. Participants should have 0 or the lowest score on four questionnaires for addiction screening and negative results on the urine cotinine test. In the initial study, participants were randomly categorized into three groups for smoking cessation. One hundred sixty-four smokers and 60 non-smokers were recruited. Participants completed questionnaires, S-HTP, and blood tests. A more detailed data collection procedure was published in primary research (xxx, 2019).

The S-HTP drawing, which can be completed on one sheet, was used to reduce the burden of participants [17]. Colors were used to facilitate free emotional expression [18]. Participants drew a house, a tree, and a person on a sheet of paper (42.0×29.7 cm) with 12 colored pencils. They also provided answers to questions including the age of the person and the tree, the kind of tree they had drawn, any cuts or dead parts on the tree, feelings toward the tree and house, gender, behavior, thoughts, feeling of a person, and a description of the people who lived in the house. Participants completed the revised Multidimensional Coping Scale and the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale. For the secondary analysis, the S-HTP drawings were taken pictures, changed to pdf files, and accustomed to the standardized vertical size (17.8 cm). Coding was performed by the researcher and a research assistant.

∙ The revised Multidimensional Coping Scale (MCS-R) was used to examine individual, social, and religious coping [19,20]. The MCS-R consists of 13 sub-domains with 50 questions. Scores range from 0~12 for each coping style, with higher scores indicating more significant use of coping skills. Cronbach’s ⍺ was .86 in this study. The permission was obtained from the developer.

∙ The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS), developed by Shiffman and his colleagues [21] and translated into Korean by Park [22], consists of 23 items with a five-point Likert scale. Inter-item consistency was .90 in 274 smokers [22]. The NDSS has eight factors that explained 58.3% of the variance [22]. The permission was obtained from the developer and a Korean translator. Only smokers completed the NDSS.

∙ Buck developed a quantitative scoring manual for the H-T-P drawings [1] that was translated into Korean [23]. The H-T-P drawing scoring consists of three categories (details, proportion, and perspective). Each category has three levels, with one to three sublevels: Defect (D), Average (A), and Superior (S). A total of 87 items were evaluated. One point is given for each item. There are two types of scores: the weighted flaw score and weighted good score. The weighted flaw score is the sum of three times the D3 score, two times the D2 score, and one time the Dl score. The weighted, good score is the totality of one time the Al score, two times the A2 score, three times the A3 score, four times the S1 score, and five times the S2 score. To check reliability, 20 subjects of S-HTP drawing were selected using a random table. If the intraclass correlation coefficient is 0.6 or more, 15 samples are required[24]. Inter-rater reliability was .80 in this study.

∙ Mikami developed the scoring system for the S-HTP based on Buck's scoring system [25]. In this study, harmonization, relations between figures, and perspectives were used to evaluate the integrity of the S-HTP. A scoring system was revised for statistical analysis. Zero-point for no harmonization, one point for drawing in a row, and two points for allover harmonization were given. Zero-point for inappropriate size between figures and one point for appropriate size between figures. Appropriate size means that the tree is bigger than a house, and a house is bigger than a person. Zero points for separate figures, one point for two attached figures, and 2 points for three attached figures were given.

The sample size was calculated using G POWER. F tests, multiple linear regression, fixed model, effect size f2 0.15, ⍺ error 0.05, power 80%, and numbers of predictors 23 were used. Cohen defined effect size f2 0.15 as a medium effect [26]. The total sample size was 166. A t-test, mean differences between two independent means (two groups), two tails, effect size d 0.5, ⍺ error 0.05, power 80%, and allocation ratio 2/1 were used. The total sample size was 144 (96/48). Smokers were oversampled to study more about the characteristics of the group. Oversampling can be used if the group is small compared to the population, or researchers want to examine more about the group [27]. IBM SPSS 23 was used for statistical analysis. The x2 test was used to examine gender and job differences. An independent t-test was used to compare differences in S-HTP scores between smokers and non-smokers. Pearson correlation was used to examine correlations among nicotine addiction, coping skills, and the S-HTP drawing scores. Multiple regression was used to determine predictors of nicotine addiction. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) used for muticollinearity diagnosis was less than 10.

Among 224 participants in the initial study, one hundred and twenty-six smokers and 60 non-smokers completed the S-HTP drawings test in this study. One hundred sixty-five participants completed the MCS-R. One hundred eighteen participants completed the NDSS. The average age among smokers was 27.04±5.59 and 24.87±1.60 among non-smokers (t=2.95, p=.004). Among all the participants, 92.9% of smokers and 100% of non-smokers were college students. Regarding gender, 95.2% of smokers and 100% of non-smokers were males.

The integrity of the S-HTP was not significantly different between smokers and non-smokers (1.90±1.39, 1.80± 1.54, t=0.43, p=.67). Normal perspectives in the S-HTP drawings were negatively correlated with emotional support seeking (r=-.18 p=.020).

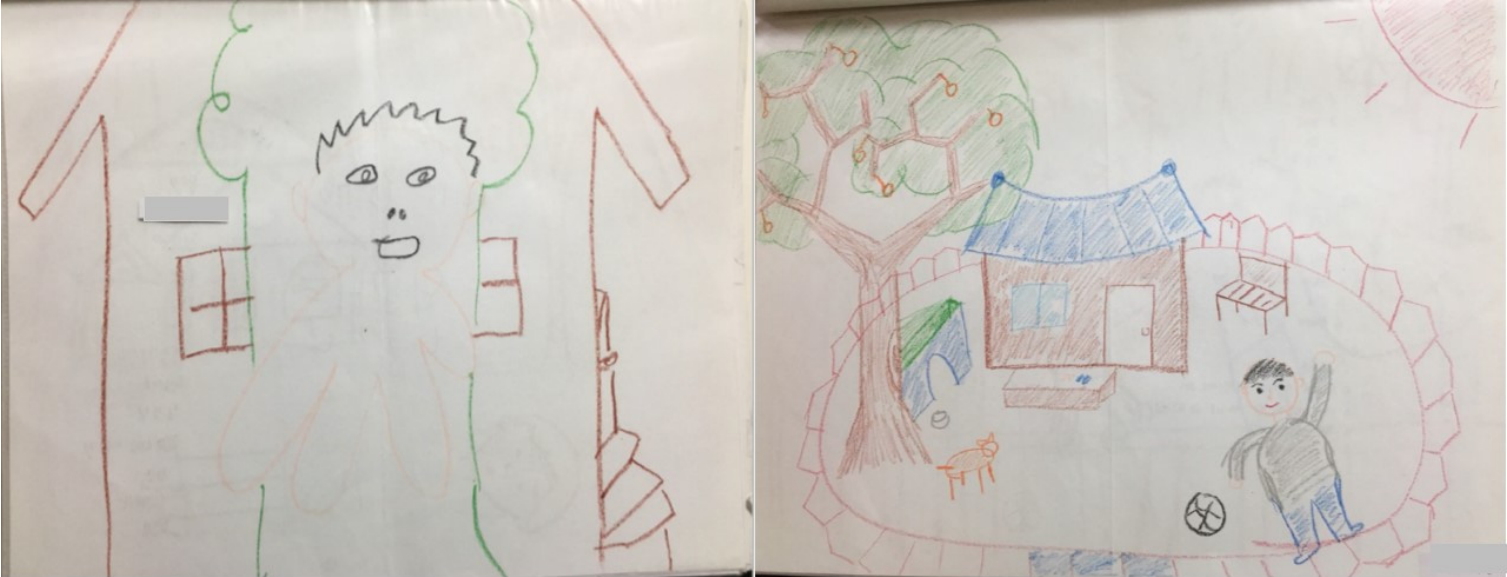

Non-smokers drew additional decoration of a house (p=.009), two-dimensional body parts (p<.001), additional decoration of a person such as a necktie, jewelry (p=.012), and proportioned body parts (p=.001) as compared to smokers (Table 1). Smokers drew more disproportionate stem and branch (p=.009) and did not draw the nose, lips, or eyes, and generally drew one-dimensional body parts as compared to non-smokers (p=.001). Figure 1 shows the differences in the S-HTP drawing between a smoker and a non-smoker. The non-smoker drew a porch and roof materials by shading. The non-smoker drew eyes with dots, a nose with one vertical line curving at its lower end, the hair on the head and eyebrows, and a two-dimensional neck and trunk of conventional shape. The non-smokerdrew a circular face, a head, and a trunk with a 1:2 ratio and proportional eyes, mouth, and nose. The non-smokerdrew a person kicking a ball. However, the smoker did not draw a neck, shoulders, hands, fingers, feet, and clothing. The smoker drew disproportionate body parts.

There were correlations between the S-HTP drawings and nicotine addiction (Table 2). Nicotine addiction was positively correlated with disproportionate parts of the house (r=.41, p<.001) and negatively correlated with the rectangular shape of the primary wall (r=-.27, p=.003), two-dimensional body parts (r=-.19, p=.041), additional decoration of a person (r=-.29, p=.001), and proportionate body parts (r=-.19, p=.038).

There are correlations between S-HTP drawings and coping skills (Table 2). Two-dimensional house parts were negatively correlated with self-criticism (r=-.20, p=.011). The central position of the house on a vertical line of a paper was negatively correlated with fatalism (r=-.16, p=.038). Rectangular primary wall was positively correlated with perseverance (r=.21, p=.008). Two-dimensional tree parts were positively correlated with religious support (r=.20, p=.009). Attachment of branch to branch was correlated with active coping (r=.24, p=.002). Disproportionate stem and branch were positively correlated with perseverance (r=.17, p=.031), fatalism (r=.20, p=.008), and acceptance (r=.16, p=.042). Missing parts of a person was negatively corelated with active coping (r=-.17, p=.025) and emotional pacification (r=-.15, p=.050). Two-dimensional body parts were positively correlated with active coping (r=.23, p=.002), while negatively corelated with fatalism (r=-.18, p=.021). Active person was positively correlated with positive interpretation (r=.18, p=.020). Disproportionate body parts were negatively correlated with active coping (r=-.17, p=.028). The proportionate body parts were positively correlated with perseverance (r=.19, p=.015) and positive interpretation (r=.18, p=.020).

Figure 2 shows the differences in S-HTP drawings based on coping skills. The S-HTP drawing on the left was by a smoker who scored three on emotional expression, one on active coping, three on positive interpretation, and five on emotional pacification. He could not quit smoking cigarettes during the two-year follow-up period. As active coping is negatively correlated with missing parts of a person and disproportionate body parts, he did not draw hairs and ears and drew one-dimensional body parts and disproportionate body parts. The right S-HTP drawing was by a smoker who scored three on emotional expression, 12 on active coping, 12 on positive interpretation, and 12 on emotional pacification. He was able to quit smoking during the two-year follow-up period. As active coping was positively correlated with a central location on a vertical line of a tree, two-dimensional body parts, and proportionate body parts, he drew a person who has proportionate body parts and fingers, hairs, eyes, lips and a tree on the central location on a vertical line. He drew the house that has a perpendicular intersection of the primary and sidewalls.

A lack of additional decoration of a person, disproportionate house parts, and a lack of proportionate body parts explained 26% of nicotine addiction (adjusted R2=.26, p< .001) (Table 3). Additional decorations of a person and proportionate body parts decreased nicotine addiction by 28% and 17%, respectively, while disproportionate house parts increased nicotine addiction by 39%. Predictors of active coping were central locations on a vertical line of a tree and two-dimensional body parts (adjusted R2=.09, p<.001). Central locations on a vertical line of a tree and two-dimensional body parts increased active coping by 21% and 20%, respectively. Predictors of self-restraint was proportionate house parts (adjusted R2=.04, p=.008). Proportionate house parts increased self-restraints by 21%. Predictors of perseverance was disproportionate body parts (adjusted R2=.02, p=.031). Disproportionate body parts increased perseverance by 17%. The predictor of downward comparison was a lack of additional decorations of a person (adjusted R2=.02, p=.040). Additional decorations of a person decreased a downward comparison by16%. Predictors of fatalism were disproportionate tree parts and a lack of central position of a vertical line of a house (adjusted R2=.06, p=.003). Disproportionate tree parts increased fatalism by 21%, while the central position of a vertical line of a house decreased fatalism by 17%. Predictors of self-criticism were a lack of two-dimensional house parts and missing parts of a tree (adjusted R2=.06, p=.004). Two-dimensional house parts and missing parts of a tree decreased by 20% and 17%, respectively. The predictor of religious support was two-dimensional tree parts (adjusted R2=.03, p=.010). Two-dimensional tree parts increased religious support by 20%.

The results of this study showed that non-smokers drew more decorative parts of a house and a person, two-dimensional body parts, and proportionate body parts as compared to smokers. Smokers drew more disproportional tree stems and branches and did not draw the nose, lips, or eyes and generally drew one-dimensional bodies as compared to non-smokers. There is a lack of studies to discuss the result of this study. H-T-P drawings by sexual offenders were characterized by a missing eye, nose, mouth, feet, hand, or facial expression [28]. Repeated studies are needed to examine the characteristics of H-T-P drawings by people with nicotine addiction.

The results of this study showed correlations among the S-HTP drawings, nicotine addiction, and coping skills. There is a lack of studies examining the correlations among S-HTP drawings, nicotine addiction, and coping skills. In a previous study, the anger and stress coping skills training for five weeks increased smoking cessation rates [29]. This result suggests that an intervention to increase healthy coping skills such as active coping, positive interpretation, and emotional pacification is needed for smoking cessation. Afolayan found that slanted houses and houses without doors, windows, or ways showed maladaptation in the H-T-P drawings in 43 children who experienced earthquake [10]. Trees with many leaves showed adaptive coping, tree drawings with holes in their trunks, as well as through cut, dead, or damaged trees showed maladaptation [10]. Further studies are needed to examine the correlations between the characteristics of H-T-P drawings and various indicators of mental health.

In this study, factors associated with nicotine addiction were a lack of additional decoration of a person, disproportionate house parts, and a lack of proportionate body parts. There is a lack of study to examine predictors related to any addiction in the H-T-P drawings. Demikhanova and his colleagues found that 78% of 20 people with computer game addictions drew a person with big eyes, and 61% drew a person with big ears. Eighty-nine percent of 20 people with computer game addiction demonstrated a tendency toward a chaotic escape from reality, and 83% had an emotional coldness toward their fathers [8]. A house drawing predicted resilience in children with trauma [11]. Six items of resilience indicators in a house drawing are “the house is accessible,” “the house appears nurturing,” “house showed cognitive complexity,” “house had windows,” “house appeared bare (reverse),” and “house had few details (reverse)” [30]. Further studies are needed to examine the predictors of nicotine addiction in H-T-P drawings.

The results of this study cannot be generalized and only applied to Korean adults. The second limitation was not analyzing the number of colors in the S-HTP drawings. Further studies are needed to examine different color choices or the number of colors in S-HTP drawings by nicotine addiction or coping skills. There is a limitation in analyzing results by recruiting twice as many smokers as non-smokers without reflecting the proportion of the population. In a future study, it is suggested that the recruitment ratio of smokers and non-smokers is 1 to 1 and divided into two groups for analysis of correlation and predictive factors. S-HTP test, one of the projective tests, unlike objective, quantitative analysis, has unique, productive responses, and the advantage of showing unconsciousness because it is difficult to defend [3]. S-HTP test helps patients to express desires and feelings freely by taking a non-verbal approach. The process of talking about S-HTP helps to visualize oneself and look at it as a separate object, facilitating insight into one's problems. Therefore, S-HTP can be used as an assessment tool and an intervention in psychiatric nursing settings [9]. The S-HTP drawing could be used for assessment for people who want to quit smoking cigarettes. During the initial assessment for smoking cessation, the characteristics of healthy and unhealthy coping shown in the S-HTP drawing can be discussed to improve smokers' motivation to quit smoking. The results of this study presented the characteristics of the S-HTP drawing by smokers and factors associated with nicotine addiction. If counselors see those characteristics in the S-HTP drawing, counselors could provide more counseling sessions for smoking cessation. Counselors can build a rapport with counselee during the interpretation of the S-HTP. By explaining the strengths and weaknesses of a person shown in the S-HTP, counselors can advise the strategy of smoking cessation. Further studies are needed to investigate the effect of the S-HTP drawing test as an intervention for smoking cessation.

Non-smokers drew additional decoration of a house, two-dimensional body parts, and proportioned body parts as compared to smokers. Smokers drew more disproportionate stem and branch and did not draw the nose, lips, or eyes, and generally drew one-dimensional body parts as compared to non-smokers. There were correlations among the S-HTP drawings, nicotine addiction, and coping skills. Predictors of nicotine addiction were a lack of additional decoration of a person, disproportionate house parts, and a lack of proportionate body parts. The results of this study showed that the S-HTP drawings were different from nicotine addiction and coping skills.

Fig. 2.

Sample S-HTP drawings of a person with unhealthy coping skills (left) and a person with lower scores on healthy coping skills (right).

Table 1.

Comparison of House-Tree-Person Scores between Smokers and Non-smokers (n=186)

Table 2.

Correlations among House-Tree-Person Drawing Test Scores, Nicotine Addiction, and Coping Skills (N=118~165)

Table 3.

Predictors of Nicotine Addiction and Coping Skills in the House-Tree-Person Drawing Test (N=118~165)

| Variables | Categories | B | SE | β | t | p | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine addiction (n=118) | Disproportionate house parts | 5.44 | 1.10 | 0.39 | 4.95 | <.001 | .26*** |

| Additional decoration of a person | -2.89 | 0.81 | -0.28 | -3.58 | .001 | ||

| Proportionate body parts | -1.82 | 0.87 | -0.17 | -2.08 | .040 | ||

| Active coping (n=165) | Central location on a vertical line of a tree | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 2.83 | .005 | .09*** |

| Two-dimensional body parts | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 2.70 | .008 | ||

| Self-restraint | Proportionate house parts | 0.46 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 2.68 | .008 | .04** |

| Perseverance | Disproportionate tree | 0.49 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 2.17 | .031 | .02* |

| Positive interpretation | Proportionate body parts | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 2.61 | .010 | .05** |

| Perpendicular intersection of primary and side walls | -0.30 | 0.14 | -0.16 | -2.14 | .034 | ||

| Downward comparison | Additional decoration of a person | -0.14 | 0.07 | -0.16 | -2.07 | .040 | .02* |

| Acceptance | Disproportionate tree parts | 0.45 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 2.05 | .042 | .02* |

| Fatalism | Disproportionate tree parts | 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 2.78 | .006 | .06** |

| Central position of a vertical line of a house | -0.23 | 0.10 | -0.17 | -2.25 | .026 | ||

| Self-criticism | Two-dimensional house parts | -0.20 | 0.08 | -0.20 | -2.62 | .010 | .06** |

| Missing parts of a tree | -0.54 | 0.24 | -0.17 | -2.27 | .025 | ||

| Religious support | Two-dimensional tree parts | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 2.59 | .010 | .03* |

REFERENCES

1. Buck JN. The H-T-P technique, a qualitative and quantitative scoring manual. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1948;4(4):317-396.https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(194810)4:4<317::AID-JCLP2270040402>3.0.CO;2-6

2. Kato D, Suzuki M. Developing a scale to measure total impression of Synthetic House-Tree-Person drawings. Social Behavior and Personality. 2016;44(1):19-28.https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.1.19

3. Fujii C, Okada A, Akagi T, Shigeyasu Y, Shimauchi A, Hosogi M, et al. Analysis of the synthetic house-tree-person drawing test for developmental disorder. Pediatrics International. 2016;58(1):8-13.https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.12790

4. Polatajko H, Kaiserman E. House-Tree-Person projective technique: a validation of its use in occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1986;53(4):197-207.https://doi.org/10.1177/000841748605300405

5. Roysircar G, Colvin K, Afolayan A, Thompson A, Robertson TW. Haitian children's resilience and vulnerability assessed with house-tree-person (HTP) drawings. Traumatology. 2017;23(1):68-81.https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000090

6. Zhou A, Xie P, Pan C, Tian Z, Xie J. Performance of patients with different schizophrenia subtypes on the Synthetic House-Tree-Person Test. Social Behavior and Personality. 2019;47(11):1-8.https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.8408

7. Yang G, Zhao L, Sheng L. Association of Synthetic House-Tree-Person drawing test and depression in cancer patients. BioMed Research International. 2019;1-8.https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1478634

8. Demilkhanova A. Comparative analysis of computer and drug addiction. International Journal of Advances in Psychology. 2014;3(1):10-13.https://doi.org/10.14355/ijap.2014.0301.02

9. Yu YZ, Ming CY, Yue M, Li JH, Ling L. House-Tree-Person drawing therapy as an intervention for prisoners' prerelease anxiety. Social Behavior and Personality. 2016;44(6):987-1004.https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.6.987

10. Afolayan A. Haitian children's House-Tree-Person drawings: global similarities and cultural differences. [dissertation]. New England: Antioch University; 2015. p. 240

11. Boogar IR, Talepasand S, Dostanian A. The prediction of resilience and social-emotional assets among preschoolers based on the House-Tree-Person™ Projective drawing. Turkish Journal of Psychology. 2016;31(77):1-14.

12. Varescon I, Leignel S, Gerard C, Aubourg F, Detilleux M. Selfesteem, psychological distress, and coping styles in pregnant smokers and non-smokers. Psychological Reports. 2013;113(3):935-947.https://doi.org/10.2466/13.20.PR0.113x31z1

13. Seo KH, Lee SM. Psychological factors associated with short-term and long-term abstention following a smoking cessation program. Journal of Korean Society for Health Education and Promotion. 2004;21(1):137-151.

14. Araujo RB, Oliveira Mda S, Pedroso RS, Castro Mda G. Coping strategies for craving management in nicotine dependent patients. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;31(2):89-94.https://doi.org/10.1590/s1516-44462009000200002

15. Lee S, Park H. Effects of auricular acupressure on pain and disability in adults with chronic neck pain. Applied Nursing Research. 2019;45: 12-16.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2018.11.005

16. Lee EJ. The effect of auricular acupressure and positive group psychotherapy with motivational interviewing for smoking cessation in Korean adults. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2020;34(2):113-120.https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000348

17. Fukunishi I, Sugawara Y, Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Kawarasaki H, Surman OS. Association between pretransplant psychological assessments and posttransplant psychiatric disorders in living-related transplantation. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):49-54.https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.43.1.49

18. Park J-R, Lee K-M. A study of interaction effects on FEATS between the K-HTP test contexts and subjects' levels of neuroticism. Journal of Arts Psychotherapy. 2016;12(2):1-22.

19. Chon KK, Kim KH, Cho SW, Rho MR, Sohn CR. Development of a multidimensional coping scale. Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1994;13(1):114-135.

20. Suh KH, Chon KK. Spiritual well being, life stress, and coping. Korean Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9(2):333-350.

21. Shiffman S, Waters A, Hickcox M. The nicotine dependence syndrome scale: a multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tobacco Research. 2004;6(2):327-348.https://doi.org/10.1080/1462220042000202481

22. Park JW, Yoon J-Y, Kim T-S, Kim SJ, Kim DJ. Standardization of Korean version of Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale and its predictive implication on nicotine cessation. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association. 2007;46(1):58-64.

23. Kim DY, Gong M. Psychological diagnosis by human drawing and House-Tree-Person drawing. Daegu: Korean Art Therapy Association; 2001 367

24. Bujang MA, Baharum N. A simplified guide to determination of sample size requirements for estimating the value of intraclass correlation coefficient. Archives of Orofacial Sciences. 2017;12(1):1-11.

25. Min K-M. A study on the formal characteristics of children with negative affectivity in S-HTP projective drawing tests. Pyeongtaeck: Pyeongtaeck University; 2010

26. Selya AS, Rose JS, Dierker LC, Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ. A practical guide to calculating Cohen's f2, a measure of local effect size, from PROC MIXED. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3(111):1-6.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00111

27. Yoo Y-S, Shin K-I. A study on the decision of sample size for panel survey design. Korean Journal of Applied Statistics. 2011;24(1):25-34.https://doi.org/10.5351/KJAS.2011.24.1.025

28. Kong M, Choi EY. A study on the comparison on the characteristics of the K-HTP response between sexual offenders and ordinary people. Journal of Arts Psychotherapy. 2013;9(4):223-241.

29. Yalcin BM, Unal M, Pirdal H, Karahan TF. Effects of an anger management and stress control program on smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2014;27(5):645-660.https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.05.140083

30. Roysircar G, O'Leary K, Colvin K. Development of the Haiti House-Tree-Person Test (H-HTP): a measure of Haitian children's resilience and vulnerability. New England: Antioch University; 2013 25

-

METRICS

- Related articles in J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs

-

Factors associated with Brain Function in Patients with Eating Disorders2023 June;32(2)